This article is part of a series and has been written by the Master’s students in Global Politics and Society at the University of Milan. As attending students of “The Welfare States and Innovation” course, they explored the connection between Social Innovation and new forms of Welfare in contemporary societies. The article highlights the development of new synergistic partnerships among actors involved in multi-stakeholder networks and innovative multi-level governance models for social policies. Here are the first, the second and the third articles of the series.

According to Istat (Italian National Institute of Statistics), the Southern part of Italy is the poorest one in terms of GDP per capita, which stands around 19,000 euros per year, a very low data if compared to the one of Northern Italy, which stands around 37,000 euros per year. In terms of disposable income per inhabitant, the regions of South Italy are still the poorest, with 14,200 euros, 60% less with respect to the North (Istat, 2019). Sicily and Calabria, in particular, are two regions of Southern Italy characterized by a poor welfare system and affected by the mafias: Cosa Nostra in Sicily and ‘ndrangheta in Calabria. Thus, this article aims to find out how movements from below, specifically anti-mafia associations, are improving the welfare system in Sicily and Calabria.

The origins of the phenomenon

As claimed by professor Maurizio Catino, “Mafia is a term that indicates a type of criminal organization governed by violence, silence, initiation rites, and founding myths” (Catino, 1997). Scholars indicate 1861 as the year of birth of mafias, in the agricultural areas of Sicily. Hence, we can say that mafias have been active in Italy for 160 years (Santino, 2008), in which they have been attacking different sectors like economy, society, and politics (dalla Chiesa, 2012). The social and civic response had been engendered immediately after, but the most modern ones have emerged right after the assassination of prefect Carlo Alberto dalla Chiesa in 1982 and of Sicilian magistrates Giovanni Falcone and Paolo Borsellino in 1992. Following a common definition of anti-mafia movement: “a type of social movement which entails a large variety of social initiatives guided by different actors in order to fight mafia and illegality in the territory” (retrieved from Santino, Centro Siciliano di Documentazione Giuseppe Impastato).

The issues at stake: low cohesion and high social risk

Our analysis, as already announced, will deal with two emblematic regions: Sicily and Calabria, as being relevant for the explicit connections between regional welfare and mafia influence in the territory.

One of the major experts in this field is Giovanni Bertin, professor at Ca’ Foscari University. He has drafted an important classification of Italian Welfare, describing the main characteristics region by region. Sicily and Calabria are addressed as regions of a Minimal Welfare type with high social critical issues (Bertin, 2012). This implies some important characteristics, such as the low presence of actors, both public and private, the low-extended supply, the weakly diffused subsidiarity. Consequently, the result is a society that is not so cohesive and where there is a high social risk (Bertin, 2012).

What data tell us about the social protection systems in Calabria and Sicily

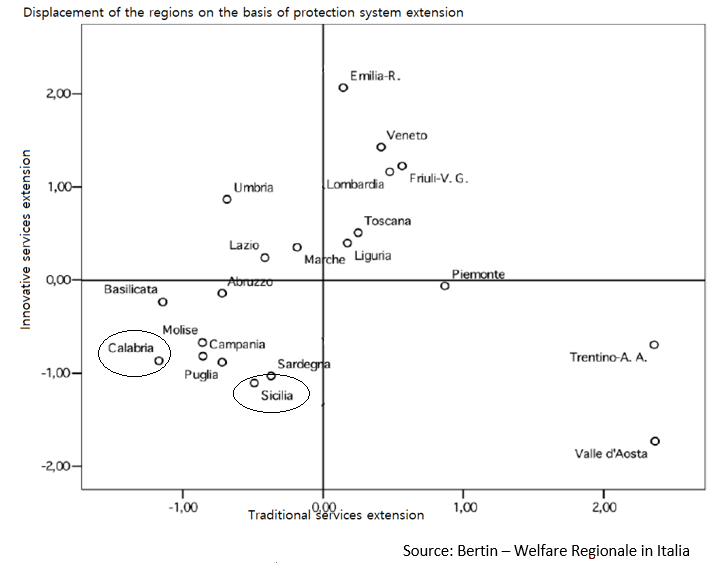

The absence of a good public fund’s management due to the lack of private and third sector actors makes difficult the delivery of social services, both the traditional and innovative ones. Indeed, looking at Bertin’s analysis (figure 1), which analyzes the displacement of the regions based on their protection system extension, there is a very low extension of traditional and innovative services in both regions that we are taking into account.

Figure 1. Displacement of the regions on the basis of protection system extension

Source: Bertin 2012

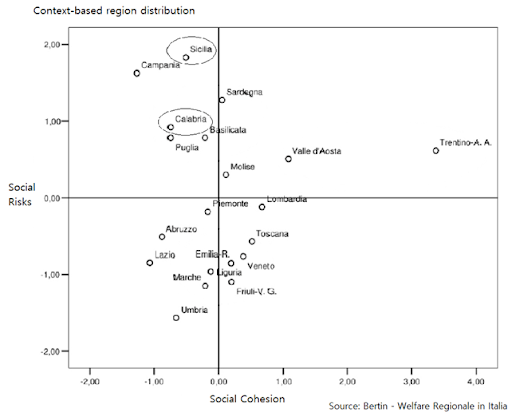

Bertin also shows that there is a link between low social cohesion and high social risks (figure 2).

Figure 2. Context-based region distribution

Source: Bertin 2012

As Bertin pointed out, services are better implemented where social risks are not so high: “There is a significant correlation between the innovative services extension and social cohesion: the lower is the social cohesion, the higher are the social risks and much lower is the creation of innovative services covered by the public regional welfare” (Bertin, 2012).

The environmental conditions for crime: the particularistic-clientelist welfare

Being so poor and with a low extension of social services, the Southern Italian regional welfare can be defined as particularistic-clientelist welfare (Bertin, 2012) based on monetary transfers, favoritism, poor subsidies in education and healthcare, scarce social welfare services, low efficiency of public bureaucracies and low involvement of company-based welfare and the third sector.

According to Prof. Pietro Fantozzi – Professor at Calabria University – a situation like this one results in an inadequate environment for the development of an ‘healthy’ welfare and social innovation, due to the high social risk already present. The environmental conditions are therefore favorable for illegal activities, through mafia management, aimed to manipulate the economic policies (Fantozzi, 2012). However, new anti-mafia movements are born in the last decades to fight against illegality and mafias and to pursue the well-being of the whole society.

Anti-mafia movements as socially innovative organizations promoting a new type of welfare?

In order to answer this question we provide a comparative analysis of two associations, Addiopizzo and GOEL – Cooperative Group, respectively in Sicily and Calabria. Going through our analysis we are going to understand if mafias really act as a barrier to social development and if, consequently, anti-mafia movements work as promoters of social innovation and improve regional welfare systems. To foster our conclusions, we have provided some in-depth interviews with Addiopizzo and GOEL managers and some of their partners.

Addiopizzo: the bottom-up reaction to Mafia

Addiopizzo is an open and dynamic movement that acts from the bottom, being the voice of a cultural revolution against Cosa Nostra. It is also a voluntary and non-partisan association, which promotes an economy free from mafia through the tool “Addiopizzo critical consumption”. Through this kind of guide, the association promotes a consumption which is clear and completely legal and aims at supporting employers who are fighting against the mafia. The association was born in 2004 from the initiative of a group of friends planning their future just after their graduation. The original idea was to open a pub in Palermo, but their feelings turned into overwhelming anxiety and worry that a criminal – on behalf of the mafia – could ask them to pay “pizzo” (i.e. extortion/bribe). The rationale behind is that – broadly speaking – those who own a commercial activity are not expected to denounce extortion if the whole society deems the crime as being normal. Consequently, they decided to change their strategy turning their message into a public complaint: on the night between 28th and 29th of June, they stuck everywhere around the city hundreds of small stickers stating that "Who pays for pizzo is a person without dignity". This became a real provocative slogan.

From this moment on, Addiopizzo has grown rapidly, creating a circuit of 1,026 businesses, 13,379 consumers who support them, 184 schools involved in anti-racket training, and 3,538 messages of solidarity from the world. The whole mechanism has been raised through free tax-exempt donations and also through regional and national contributions, which are the main source of the association’s financial support.

Aims and purposes of the association

The primary aim of the association – according to its statute – is to protect the right to lawfulness and the free exercise of business activity, without criminal pressure, and to guarantee the interests and prerogatives of citizens-consumers and dealers who oppose the extortion. Addiopizzo also plans and fosters activities that are aimed at promoting the birth of an anti-mafia and anti-racket movement among citizens in Sicily: Addiopizzo’s activity represents the duty of civil society to play an active role alongside dealers in the fight against mafia racket.

The successful idea: Caffé Verdone

An example of the success of Addiopizzo is the social initiative of the Caffè Verdone, a pub in Bagheria (near Palermo). The idea was born from the awareness that although it was hard to denounce extortion before the Pandemic, then it became almost impossible due to economic difficulties. The project was designed by Addiopizzo together with the pub’s owners, who were suffering the consequences of the Pandemic and have denounced the extortion also thanks to the association. The outcome was a national critical consumption campaign operating on all social media as a sort of “acquisto sospeso” (literally: suspended purchase), since the Neapolitan tradition of paying a coffee to those who can’t afford it, leaving it at the pub and waiting for someone to request it. Here, the acquisto sospeso refers to the purchasing of something from all over Italy, allocated to families living in conditions of poverty and marginalization. In this way, the initiative has become fundamental in the fight against racket but also a useful tool of social inclusion in a period of difficulty and precarity.

The community building to fight mafias: the GOEL-Cooperative Group

GOEL-Cooperative Group was born in 2003 in the Locride area as a community of businesses with the aim to create redemption paths in Calabria. In the words of the founder Vincenzo Linarello, “GOEL is a biblical name which means redeemer”. GOEL is a community of people, families, different groups and companies: 12 social enterprises, 2 agricultural cooperatives, 2 voluntary associations, 1 foundation, and 29 companies.

GOEL aims at promoting legal work, social promotion, opposition towards every kind of strong power guided by violence, oppression, manipulation, and social control. Their work ethics involves values such as freedom, meritocracy, equal opportunities, solidarity between communities, active non-violence, protection of the environment, freedom of the market and competition, transparency, and cooperation between the different realities that compose GOEL.

Aims and purposes of the Cooperative Group

GOEL intends to protect single individuals so that everyone has the possibility to change. One of the key concepts of their values is the co-winning logic: the belief that the paths of ethic changing must be a victory for everyone. Indeed, the real and lasting changes are those that do not produce winners and losers, but where everyone wins together.

GOEL supports the vision of a democratic State established on the participation of all citizens, built on the criteria of vertical subsidiarity, according to which the main actor of decision-making process is the community. GOEL promotes effective ethics: ethics must be both fair and effective and it must be evaluated based on its ability to solve social issues without engendering new ones

The Cooperative Group’s projects to fight against mafia: the brand “CANGIARI”

As a Cooperative Group, GOEL implemented several projects in order to pursue its purposes. One of these is “CANGIARI” (a word that means “changing” in the Calabrian dialect), which is a brand born to preserve the tradition of ancient weaving. It is based on environmental and social sustainability: CANGIARI is the first high-end fashion brand entirely ethical, completely made in Italy and produced with 100% bio-materials. CANGIARI plays a central role in boosting integration and inclusion of disadvantaged people. As pointed out by Linarello, the brand’s President, almost 90% of CANGIARI workers are female and this shows that the combination of tradition and innovation can be achieved if guided by ethics and social values.

The pursuit of social innovation: raising awareness and building multi-stakeholder networks

This research underlines some differences between the two regions and related associations. Addiopizzo was born to give legal assistance to entrepreneurs that denounced the pizzo, and to allow entrepreneurs to work freely; whilst GOEL tries to create work with the aim to re-evaluate the territory. Nevertheless, there are many similarities between Addiopizzo and GOEL, since they have similar aims. They both reach their aim of fighting mafias at a local level, raising awareness in the local area and building a multi-stakeholder network, which brings different associations and projects together. As a final result, they are able to improve regional welfare through innovative means.

Anti-mafia movements as drivers of social innovation?

In conclusion, we claim that the meta-analysis, as well as the in-depth interviews, corroborate the hypothesis that anti-mafia movements can be defined as social innovators. Trying to reach their aim, they get necessarily involved in social innovation and, therefore, they are improvers of local welfare.

In addition, the way in which mafias are conceived today has completely changed: it is no longer perceived as a juridical matter, but even as an economic, social, and gender issue. Indeed, mafias broaden the area of social risks and needs, because they take root where there is a lack of institutions and social welfare services. Instead, anti-mafia associations improve social inclusion, boosting social cohesion by creating new forms of welfare, and becoming an alternative to illegal “welfare” services provided by mafias. Of course, there is still a long way to go: in this path the State needs to collaborate with private actors who already work on the improvement of living conditions in Southern Italy.

References

- Avviso Pubblico (2018), Il movimento dell’antimafia sociale: l’analisi della Commissione Antimafia

- Bertin G. (2012), Welfare Regionale in Italia, Venezia, Edizioni Ca’ Foscari

- Catino M. (1997), La Mafia come fenomeno organizzativo, in “Quaderni di Sociologia”, 14, pp. 83-98

- dalla Chiesa N. (2012), L’Impresa Mafiosa. Tra Capitalismo Violento e Controllo Sociale, Milano, Cavallotti University Press

- Fantozzi P. (2012), Il Welfare nel mezzogiorno, in U. Ascoli (a cura di), Il Welfare in Italia, Bologna, il Mulino, pp. 283-304

- Germoni A. (2009), Carovana Antimafia, Libera Conferenza, 5 novembre 2009, Macerata

- Santino U. (2008), Breve Storia della Mafia e dell’Antimafia, Trapani, Di Girolamo